This week in “WTF is up with that graph”

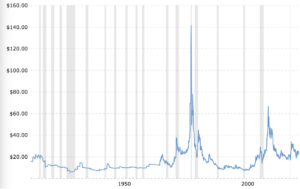

While researching the investment thesis for buying silver, I stumbled upon this chart showing inflation adjusted silver prices.

When I saw this graph I became quite curious. What in the world could have caused that giant spike in 1980? The price of silver went from about $23 to $140 in three years before crashing dramatically. I expected to find a story about a silver craze or perhaps a war in a country that mined significant amounts of silver. But I discovered something far more surprising. This spike was not driven by mania of the general public, or by wars, nor by any of the other usual forces. In fact, the entire silver bubble was caused by just two individuals.

The people in question were the Hunt Brothers.

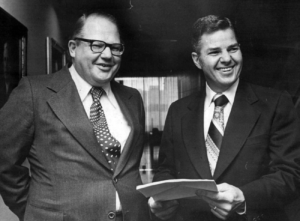

Nelson Bunker Hunt and his brother William Herbert Hunt. Source

The Hunt brothers were sons of a wealthy Texan oil dynasty. The patriarch of the family, H.L. Hunt, made a fortune in the Texas oil business. For a brief period in 1960, H.L. Hunt had been the richest person in the world. When he died, he left the sons a substantial inheritance, which they believed was at risk of being destroyed by increasing inflation.

The more I dug into this story, the most interesting it became. The Hunt brothers were involved in all kinds of financial bubbles and scandals throughout the 1970s. In 1977, the brothers purchased the rights to one-third of the US soybean harvest, were taken to court for wiretapping, got sued by the CFTC, and were charged with obstructing justice.

Bunker Hunt (the eldest of the children of H.L. Hunt’s first marriage) played a significant role in the discovery and development off the then largest oil fields in the world in Libya, making him the richest man in the world, worth an estimated $16 billion. Most of that was lost when Muammar Gaddafi nationalized the oil fields in 1973.

But those minor escapades would be dwarfed by their escapades in the silver market.

Dragon’s Hoard

Silver Bullion of the type purchased by the Hunt Brothers

In 1973, brothers W. Herbert Hunt and Nelson Bunker Hunt began their silver buying spree as a hedge against inflation, the rate of which had been steadily increasing since the 1960s. Their initial outlay was quite significant: in 1973 alone they purchased 35 million ounces via futures contracts.

The Hunt brothers had a fairly simple investment thesis; they believed silver was undervalued relative to its more famous cousin, gold, and that owning silver instead of US dollars would serve as a hedge against coming hyperinflation. The brothers believed that, with the gold standard gone, the government would keep printing money at an ever-increasing rate to pay for its expenses, and that this would lead to dramatic inflation.

One logical way to protect assets is to buy stocks or property. But, either due to some quirk of personality or a congenital belief in the value of precious metals, the Hunt brothers were not very interested in owning stocks beyond those they already held in the oil companies started by their father.

Another way would be to buy gold. But the Gold Reserve Act, passed by the Rosevelt administration in 1933 and not repealed until 1975, made it illegal for anyone but the government to possess gold.

So the Hunt Brothers turned to the next best metal: silver. Over the course of the decade, they bought tens of millions of ounces of silver. As the decade wore on, the brothers began to gain interest in a new financial instrument that would allow them to buy even more silver; derivatives.

Going Infinite

A futures contract works like this: suppose you want to buy silver because you think its price is going to go up. You might not want to deal with taking physical delivery and putting it in a vault somewhere. So instead of buying silver and transferring it from my vault to your vault, you might buy the right to purchase silver from me at some future date. Since you’re making a bet on the price of silver, you want to lock in a price NOW at current prices so that you can buy it at a discount later once the price goes up.

So I sell you the right to buy a million ounces of silver at $10 per ounce in three months time. When the future expires, you have to pay up and take delivery of the silver.

Futures contracts are neat because they allow you to exercise enormous leverage. Instead of buying a million dollars worth of silver for a million dollars, you can buy the right to purchase 10 million dollars worth of silver in the future for a million dollars. This is because to buy the futures contract, you only need to put down a small portion of the final purchase price of the silver (in this case, 1 million / 10 million, or 10%). The small deposit of 10% is called “margin”, and will play a very important role in the story of the Hunt Brothers.

If, in three months, the price of silver goes up to $15 per ounce, you can buy silver for $10 per ounce, sell it, and pocket the difference. If you bought $10 million worth of silver futures, you could earn a profit of $5 million from your $1 million, an incredible 5x return. This is a far greater the 1.5x profit than one would have been able to earn by simply buying the silver outright.

Towards the end of the 1970s, the Hunt brothers became very interested in these types of trades. They started buying futures contracts at a stupendous rate. In many cases, the Hunt brothers didn’t even need to put down a 10% margin on their futures trades. Instead, they were able to get banks to promise, on their behalf, that the money for margin would be available if needed.

The cost for such a letter of credit? Just 1% of the value of the silver in the futures contract.

This strategy allowed the brothers to reap enormous profits from just a small increase in the price of silver. But the flipside was that if prices declined even slightly in value, they could quickly lose all their money.

For normal investors, that’s pretty much where the story of futures and forwards ends; the price of the commodity is driven almost entirely by other market participants, so the bet made with a futures contract mostly hinges on their behavior.

But the Hunt brothers were so unbelievably rich that they could significantly affect silver prices BY THEMSELVES. So although they weren’t nearly rich enough to buy all the silver in the world, they were rich enough to buy the right to purchase almost half of it. With that level of control, they could force those that used silver for industrial applications to buy from them at exorbitant prices. They could nearly “corner the market”.

To profit even more, the Hunts partnered with two Arab sheiks and a group of anonymous investors working through a Swiss bank, who also began buying silver. As prices rose, they used cash settlements from their futures contracts to provide the margin necessary to obtain new letters of credit from banks to open even more futures contracts.

By the time silver hit its peak, the Hunt brothers owned 195 million ounces, which represented somewhere between 1/3rd and 2/3rds of all the silver that had ever been mined in the world at the time.

People started to notice

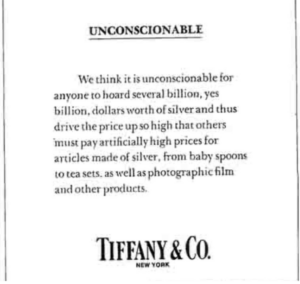

The incredible rise in silver prices did not escape the notice of the general public. Tiffany & Co, the famous New York jewelry company took out an ad in the New York Times calling out the Hunt Brothers and other silver speculators.

Source

Other articles described the effects on society at large:

“In the U.S., people rifled their dresser drawers and sofa cushions to find dimes and quarters with silver content and had them melted down,” says Pirrong, from the University of Houston. “Silver is a classic part of a bride’s trousseau in India, and when prices got high, women sold silver out of their trousseaus.”

According to a Washington Post article published that March, the D.C. police warned residents of a rash of home burglaries targeting silver.

Don’t piss off people who can change the rules

All this disruption started to irk some very important people. Among these was James Stone, chairman of the CFTC. Stone was concerned that the Hunts silver trade had become so large that it posed systemic financial risk. Should they default on their loans, it could threaten the stability of at least one major brokerage house, triggering a financial panic in the commodities markets.

Stone began to pressure brokerages to raise margin requirements for silver futures & forwards, and asked banks not to lend more money to the Hunts. In the Fall of 1979, The Chicago Board of Trade took steps to limit the number of contracts any individual investor could hold. Both they and Comex, a commodity exchange with which the Hunt Brothers had been doing business, raised margin requirements as well.

But it was not enough. Prices continued to rise through the new year, to a high of $50/ounce, or $184 in 2023 dollars.

At this point the exchanges, at the urging of Stone, began to take drastic measures to limit silver speculation. “Down Payments to control contracts were raised dramatically, no one was permitted to add to his position and big holders were ordered to begin a steady dismantling of their holdings.”

At the same time, the Federal Reserve was engaged in dramatic interest rate hikes in an attempt to combat double digit inflation. Between Jan 1979 and Feb 1980 during the peak of the bubble, the fed raised rates from 10% to 14%, making borrowing significantly more expensive.

Together, these significantly curtailed the Hunts silver buying ability, causing prices to swing wildly up and down for the next few months.

On March 27th, known as “Silver Thursday”, the Hunt Brothers missed a $100 million margin call to Bache Brokerage, precipitating a single day drop in silver prices of 49%.

At some point in 1980, Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volker became so concerned about the potential financial panic caused by the collapse of the Hunt Brothers silver bubble that he personally authorized a $1 billion dollar loan, the funds from which were used to pay off many of the brother’s creditors.

The fallout

Over the next decade, the empire built by the brother’s father slowly collapsed around them. They sold off most of their assets to repay debts and unwind their silver trades. They paid $160 million in taxes to the IRS, fines to New York for conspiring to manipulate the price of silver, and billions to lenders.

By 1986 they had declared corporate bankruptcy, followed by personal bankruptcy two years later.

The Hunt brothers remained rich thanks to a trust set up by their father that was untouched by the series of lawsuits that followed the collapse of their silver empire. In 1995, Bunker’s personal trust was estimated to be worth $175 million, and William Hunt’s trust was estimated to be worth a similar amount.

Nelson Bunker Hunt would survive another 34 years, dying in 2014 at the age of 88. William Herbert Hunt is still alive at 94, living with his wife and children in Dallas.