The first large Ponzi scheme in recorded history was created over 150 years ago by Adele Spitzer in Germany. Since then there have been dozens if not hundreds of copycats, with a recent explosion caused by the proliferation of such schemes in the form of cryptocurrencies or related shenanigans.

Ponzi schemes are deceptively simple. You’d think that after 150 years of losing money, humanity would have developed some kind of cultural immunity to losing money this way. But much like a virus they tend to look a little different every time they pop up.

The form of Ponzi schemes changes over time to suit the psychological vulnerabilities of the population it seeks to victimize. And like a virus disguising itself with an innocuous-looking coat of proteins, Ponzi schemes wrap themselves in the shawl of legitimate enterprise. The biggest Ponzi schemes can be exceptionally difficult to identify without access to privileged information.

Wait, how does a Ponzi scheme actually work?

At its core, a Ponzi scheme can be described as taking money from Peter and giving it to Paul. Whereas standard investments achieve returns through investment in growing, profitable enterprises, Ponzi schemes generate returns by issuing an ever-increasing number of claims on a fixed pool of money. When an investor decides to withdraw (which hopefully doesn’t happen too often), they receive their original investment plus a chunk of other people’s money.

The libertarians in the audience might be smirking at this point because the above description sounds an awful lot like fractional reserve banking. The two share one common feature: there are more claims on deposits than there are actual deposits. But two key differences distinguish a fractional reserve bank from a Ponzi scheme:

- A fractional reserve bank (hopefully) invests user deposits in actual productive enterprises, the ownership of which can be sold to generate liquidity in the case of unusually high withdrawal volumes.

- In most modern countries, fractional reserve banks are backed by a federal reserve, which acts as a buyer of last resort in the case of bank runs. The federal reserve will buy quality assets from the banks if they need emergency liquidity. In a fiat system, this reserve bank has the legal right to print money to buy assets in such cases.

Banks can still fail of course, and they often do. But those failures usually come about as the result of bad investments of user funds, rather than outright fabrications about the nature of the enterprise. This difference explains why banks usually last decades to centuries, while Ponzi schemes usually collapse within just a few years.

Olympus DAO: How to recruit stupid investors

Not every Ponzi scheme is deceptive. Some, like Olympus DAO, a crypto Ponzi that reached a market cap of $3 billion dollars before its collapse, are nearly completely transparent about what they are doing and how they are doing it. Olympus DAO offered returns of 4500%, a hilariously impossible rate of return which (all things considered), it sustained for an impressively long time through the use of propaganda like the (3, 3) meme.

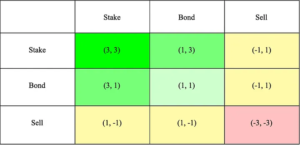

(3, 3) was a meme that was supposed to describe the game theoretic payouts for OlympusDAO participants that depended on the behavior of other investors.

Source: OlympusDAO Medium article extolling the virtues of not selling your tokens.

The idea was that if everyone bought OHM tokens and no one sold, the payoff for participants would be (3,3): they could all get rich. If a sufficient number of people defected (which here means selling OHM tokens), the payout would be (-3, -3). In reality, everyone got screwed except for a few people who got in early and sold before the peak.

You might have just finished reading the paragraph above and thought to yourself, “That’s the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard.” But to do so would be to misunderstand the function of stupid memes like (3, 3). The meme is stupid precisely to ensure people like you do not get involved in the Ponzi. It functions as a filtering mechanism to ensure that as many of the investors as possible are unquestioning enthusiasts. The last thing a Ponzi scheme wants is a lot of intelligent investors asking where all the money is going.

Olympus DAO was able to do this more or less in the open because the creators of the project managed to remain anonymous (or at least they did at the time — it’s possible that at least one of them will be unmasked in a lawsuit filed by one of the project’s early promoters).

The Ladies’ Deposit Company: How to find product market fit

Ponzi schemes inevitably stumble across many of the same techniques used by legitimate businesses to recruit customers; namely, the ones that destroy a lot of value are good at finding and recruiting a specific population with a problem to solve.

When Sarah Howe, a fortune teller in Boston, decided to create a Ponzi scheme in the 1870s, she named it the Ladies Deposit Company and targeted a population of single women, widows, and divorcees as her first customers. At the time, most banks required permission from a husband or father to open a bank account, so Sarah targeted that population in particular that was so inadequately served by the existing banking system. In modern Silicon Valley parlance, these were Sarah’s first “power users.”

This was an excellent choice, since not only were women unfairly excluded from the banking institutions of the time, but they were also generally less knowledgeable about finance due to a general societal belief that it was unnecessary to teach them. Women were the perfect target group for banking scams in the 1870s, and Sarah Howe managed to accrue about $15 million dollars of deposits (inflation-adjusted) before her scheme was ultimately discovered.

Bernie Madoff: How to foster investor envy

Bernie Madoff is perhaps the best known of all Ponzi schemers. At its peak in 2008, his Ponzi scheme held $65 billion in paper assets and $20 billion in real cash (which comes out to about $90 billion in paper assets and $28 billion in cash when adjusting for inflation). Madoff’s investment fund was the biggest classic Ponzi scheme in all of recorded history.

The most convincing lies are those that mix in truth. Bernie Madoff had a well-earned reputation as a wall street market maker who pioneered the early use of computers to facilitate trades and reduce settlement times. In the 1970s, his market making operation was able to reduce settlement times from an average of 18 days to an average of 3 days — a feat that drove institutional customers to his operation in droves.

He was a founding member of the NASDAQ, an exchange that today facilitates the exchange of shares in Microsoft, Apple, Alphabet, Tesla, and many others. He was appointed to the board of directors of the NASDAQ and had connections at the SEC and throughout the investing world. All of these legitimate accolades earned him the trust of investors who were far far more sophisticated than the (3, 3) memers of Olympus DAO. In fact, they earned him something far more valuable than trust; they earned him envy.

Madoff’s investment fund was a highly exclusive club. You couldn’t just ask for him to invest your money. You had to know someone. You had to be introduced by the right person. Madoff frequented an exclusive golf club during the winter in Palm Beach Florida.

The club hosted a who’s-who of New York finance. Madoff seems to have joined for two reasons: firstly, so he would have social access to a rich and powerful set of potential investors, and secondly, to further the appearance of luxury and exclusivity that was such a powerful tool for recruiting new investors to his Ponzi scheme.

Leonid Feldman, a rabbi at the Temple Emanu-El in Palm Beach, described the aura Madoff created around his investment fund like this:

From what I remember, people said, “It’s impossible to get in.” Somebody would come and say, “I want to invest a million dollars.” He says, “No.” He would turn people down. He created this excitement that you had to go through somebody who knows somebody who knows somebody, maybe he will take your money. He did you a favor to take your five million dollars. He was brilliant.

Why do people keep starting Ponzi schemes?

When Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi scheme collapsed in 2008, he was publicly disgraced. He lost the fortune he spent 30 years creating through his legitimate market-making business. His sons refused to speak to him for the remainder of his life. His wife lost her home, his son committed suicide, and he spent the remaining 13 of his life in prison before dying of chronic kidney disease in 2021.

When Sarah Howe’s third Ponzi scheme collapsed, she spent the remaining years of her life in poverty, living on her husband’s military stipend and telling fortunes for 25 cents each when that was not enough to cover the bills.

It’s rare to find a Ponzi scheme that ended happily for the person that started the operation. So why do people keep starting them?

The answer seems to be a combination of desperation and short-term thinking. When Adele Spitzeder started the first large Ponzi scheme in recorded history in 1869, she did so because her acting career had taken a turn for the worse and she was in massive debt to various banks. She recruited her first investor with a simple lie, stating that she knew someone who would give the lender 10% each month on her investment of 100 gulden (about $30,000 in today’s dollars). When she promptly paid the interest the following month, her first customer was very happy, and after several more months of this decided to invest additional money (and told her friends about the scheme).

Bernie Madoff, likewise, seems to have begun a Ponzi scheme after a series of bad investments forced him to either lie about his returns or admit that he had lost his friends’ and family’s money.

Of course, some people start Ponzi schemes knowingly and simply abscond with the funds after some period of time. OneCoin, a scam that took advantage of the cryptocurrency craze to sell people on a Ponzi scheme in 2015, ended in exactly this manner. Ruja Ignatova, the public face of the project and largest beneficiary of the scam, has still not been located by authorities. There is currently a $100k reward outstanding from the FBI for information that leads to her arrest.

Is Bitcoin a Ponzi scheme?

When Satoshi Nakamoto published the Bitcoin whitepaper in 2008, it was clear that he hoped it would be used as a form of digital money which could facilitate transactions without the need for government permission.

Bitcoin has mostly failed to live up to that vision, largely because vested stakeholders have prevented its underlying technology from developing to facilitate exchange. The Bitcoin network is still capped at 7 transactions per second, which means it would take about 36 years for every person in the world to perform a single transaction on the network. Payment layers like the lightning network have low rates of use and appear unlikely to result in the widespread use of Bitcoin as a means of payment. Instead, Bitcoin mainly acts as digital gold: a scarce store of value whose valuation is completely unanchored from any fundamental analysis.

For this reason, many critics of Bitcoin (and cryptocurrencies more generally), refer to Bitcoin as a Ponzi scheme. In some sense, this critique is warranted — like a Ponzi scheme, investors in Bitcoin can only get rich at the expense of others. Though Bitcoin can facilitate a limited amount of commerce, nearly all of its value is derived from people’s collective belief that others will be willing to pay more for it later.

But there is another very important sense in which Bitcoin is NOT like a Ponzi scheme: Bitcoin can never become insolvent.

Every true Ponzi scheme ends the same way: investors get spooked (often by someone discovering that the investment is a fraud), and there is a run on the bank as investors try to withdraw what they are owed. Since every Ponzi scheme is insolvent, this is impossible, and the scheme collapses when it runs out of money to pay back investors.

This cannot happen with Bitcoin because there is no pot of money. There is only Bitcoin. The price is and forever will be what the next person is willing to pay for it. So though Bitcoin goes through boom and bust cycles, the lack of insolvency risk means that no matter how many times it collapses, the potential for another future bull run will remain.

Though Bitcoin may not be a Ponzi scheme, people have managed to build regular Ponzi schemes on top of it. Celcius, a crypto lending platform that collapsed in July of 2022, offer investors up to 8.8% interest if they deposited their Bitcoin to a Celcius controlled account. When Celcius was not able to generate those returns through lending, they kept the platform afloat for a while by simply issuing more claims on crypto than what they actually held, in classic Ponzi style.

My hope is that as time goes on, the irrational mania around cryptocurrencies will abate and enthusiasm for the crypto casino will be surpassed by positive-sum use cases of blockchain like low-fee remittances and trading real-world assets. In the meantime, we will continue to gamble and fall for Ponzi schemes as our fathers did before us.

Written by Chase Denecke, Technical Writer at BlockApps